Thinking About Logic and Rationality

Thinking about Logic and Rationality: Thoughts on a book by Robert Hanna "Rationality and Logic," MIT Press Jack Leissring, Santa Rosa, CAThis effort results, it seems to me, from my reaction to a response from Robert Hanna. Thus a true dialectic and also a manifestation of what happens (to me) at an intersection with a life event. As I have considered his ideas, now for many years, the chance discovery (!) of a little book by Roger Poole titled: "Towards Deep Subjectivity" changed my understanding of the world in significant ways. Poole focuses upon the events of the 'Sixties' a time when as Andre Gregory says, in the libretto to "My dinner with Andre: " In fact, it seems to me quite possible that the nineteen sixties represented the last burst of the human being before he was extinguished."

In short, Poole's assertion suggests that "objectivity" is a will O the wisp, an hopeful, but imaginary state of being, difficult--nay, impossible to prove the existence of. Poole also appears to describe the activities--the processes--which go on in any encounter with the 'world.' My younger days imagined this as a Darwinian algorithm, inserted through time and experience into the animal (and amazingly, the plant) to protect it from predators or from unexpected potentials. The encounters yield ethical or moral responses, responses which form the shape of our actions and reactions. Poole demonstrates this using photographs of historical events--again, one picture and the myriad words.

The list of philosophers chosen by Hanna in his book "Rationality and Logic," (MIT Press) conforms to my own in many ways, while I might add George Lakoff (Mark Johnson and Rafael Nunez) to Chomsky, Quine, because of his association with Ullian and his little book: "The Web of Belief," other early Greek thinkers added to Aristotle, and Goethe to Kant.

Kant has always been a problem for me; no, not Kant the writer/man, but the effluvia, the crowd of loyalists who appear to surround an idea of him. Strangely Christ-like and likely as much a fable as Christianity. Yet, I don't know. Do we humans have a tendency to adoration? Was Levi-Strauss correct in describing our triangular tendencies: to place at the apex the tribal leader as the rest of the tribe occupy the area of the triangle?

Let me see if I can 'diagram' the path that has led to here--to this essay whose end-point I cannot foresee. Bob Hanna, an academic philosopher with a host of admirable characteristics, teaches and writes from the University of Colorado at Boulder. He is a writer whose style very much appeals to me; in the truest meaning of the idea that surrounds a dialectic. His writing implies that the reader is sitting across from him in a coffee shop and they are having a conversation. Would that other academics adopt such a form, the world would be a better place.

Hanna confesses what he is and is not: "I am a philosopher who by virtue of a deep interest in human rationality is also deeply interested in logic and cognition, I am neither a professional logician nor a professional cognitive psychologist. So I want to make it very clear in advance that I am drawing and relying even more heavily than is usual for philosophers on the theoretical expertise of others." Because Hanna's book is titled: "Rationality and Logic," MIT Press, 2006, I make here the assumption that by rationality in a sentient human he means that this person (or animal) is acting/behaving because of reasons to do so. I must say if that is his definition for the word, then we are off to a bad start: there are countless individuals who are guided by nonsense. So let me assume Hanna means that the person (or animal, or plant!) is acting rationally if a reason is based on strong evidence--in short empiricism.

Hanna also abstracts from diversity: Goya (the artist) and Pascal (the thinker). I must describe myself here: at one time I had strong attractions to a life of academic science--medical science. Even in medical school my tendencies were towards attempting to answer questions raised by biological observations. Before graduating from medical school in 1961, I had completed four "significant" papers that concerned some of the earliest forays into immunology, both animal and human. The papers won me a Borden award for undergraduate research, so, there was, at least, potential. Rites of passage included internship, movement of mind and body to another geographic place, an awakening to the "sixties" in California, quite next to where it was happening in Berkeley, and finally entering the hallowed halls of Stanford, where I spent the next four years learning and watching what was the essence of academia. 'Nay nay' I said to myself. While the possibilities were enticing, and, I could see myself at least in a rank amongst the professors and teachers, there appeared a shadow between what I felt myself to be and what the constraints of place and group seemingly demanded. The ideation was pure metaphysical. So, I never did the experiment and I admit I acted upon a form of rationality and logic in forming my choice. Of course there was the ghost of Poole looking over my shoulder as I must have made my ethical and moral choices from the encounter with this academic world I was watching.

As they say: " Things happen." The empiricist in me sees now, almost 65 years later, that I must have, in my own way, done the experiment and generated a life that was both (apparently) satisfactory, much larger than a life constrained to academia, quite rich, filled with joy, disappointments, love and fear, but definitely focused upon several "non-academic' parts of the world: art, music, architecture, and thinking.

It is apparently "thinking" that brings me to this essay, for what I think about is usually the question "why?" It started very early if memory serves--and memory itself is part of the thinking processes and the attempts to understand things. I would like to know "why" everything happens. This may be a wish that can never be known, for it fits into the ideation of a grand theory of everything, an idea that many of the modern theoretical physicists hope to achieve. Let me also at this point introduce another member of the group of advisors of whom I spoke earlier: Harry G. Frankfurt, a philosopher from Princeton who wrote a little book of significance: "On Bullshit." Included in the early part of the book is this: "One of the most salient features of our culture is that there is so much bullshit. Everyone knows this. Each of us contributes his share." I imply nothing by this inclusion, and yet. . .

So, I intend to wander through the woods, so to speak, of "Rationality and Logic" and to see if I may have wandered awry during my life of whatever it has been. Indeed, I should say I will be wandering the pathway of the labyrinth of rationality and logic and will have something to say, probably too much, about what I am currently accepting as my position in the web of belief.

It is clear to me that my place in this world is dependent upon a foundation, just as a building depends upon its foundation roots to achieve its being. I may have discussed most of these things that I am about to revisit in the form of a large series of books that I have written and published--currently 41 to date. Of course I took my own path as I have done with almost everything; I was not interested in the capitalistic/monetary rewards, rather, I imagined these books as a way to clarify my thinking, to create an object of artistic worth, and to place somewhere my "self" in a position where it could be studied, were that of interest to anyone, but mainly for my sons.

Today, while thinking about this project, I recalled a movie once watched that concerned a woman teaching in a university who adopted the point of view that it was not necessary to study the ancients: the Greeks and German philosophers and writers, but that one could start more recently; she believed the result would be the same.

This is an intriguing idea. Google, which seems to have devolved into another profit-based tool, has lost its ability to search for arcane and curious entities: my attempts at describing my goal resulted in useless outpouring. I thus asked my movie buff friend. We shall see who wins this one.

Let us adopt for purposes of this discussion--for I feel as it I am having a discussion of sorts with you and Bob Hanna--the accuracy of the assertion (mine) that the study of philosophy is the history of ideas. Let us also accept the assertion that each of us is grounded in some way by exposure to dogmatic influences in the form of what we accept as our education. Those who attend primary schools sponsored by religions are taught the tenets of those religions. Bob Hanna, in a response to a critique I made about Zeno's Paradox used the following phrase: "I completely agree! that the Logical Empiricists' conventionalist theory of logic--& that's what you would have been taught as an undergraduate--is nothing an empty game;" I want to focus on the implications of the phraseology for it coincides with some of the ideas I am discussing here. The phrase "would have been taught," carries with it the potential that "I would have learned." And yet, because of my nature--a sceptic, I in fact accepted A. J. Ayer's (1937) point of view through my own study: Dr. Ramsperger, taught the course at Wisconsin (Madison) and who wrote the text "Philosophies of Science" (Crofts, 1942) which was used to some extent in the course. Even as early as 1942, Ramsperger described his view that "Logical Positivism" had run its course.

Here, I include the opening remarks from Ramsperger's book: "Philosophies of Science," Croft, 1942: "IT IS FORTUNATE for mankind that it is possible to have knowledge without being clear as to what knowledge is. If the scientific conclusions by which we direct our lives had to wait upon the philosopher's assurance that they were based upon the correct theory of knowledge, that the subject matter dealt with is real, and that certain postulates such as causal determinism are justified, man would probably have perished from the earth while science awaited its philosophical credentials. There can be science without a philosophy of science.

Nevertheless, the inquiring intellect desires not merely to know, but also to understand what knowing is; and it is not unlikely that a scientist will make advances in his particular field as a result of clearer insight into what science is. As for those who are not specialists in science, but who wish to take advantage of anything that science has to offer toward achieving a desirable way of life, it is important that the nature of scientific knowledge be not misunderstood. That is why those who are not professional scientists, as well as those who are, may profit from a study of the philosophy of science. If spectacular scientific advance has not been accompanied by a corresponding achievement in human values, the lack of an adequate philosophy of science may well be largely responsible.

The philosophy of science is not a synthesis of the results of the various sciences. When theories are formulated which bring into one system the less comprehensive laws of separate sciences, it is the scientist who formulates them, not the philosopher. Neither is the philosophy of science speculation about possible answers to unsolved problems at the frontiers of science. Here too it is the scientist who is in a position to frame suitable hypotheses, capable of being tested by scientific methods. A book on the nature of scientific knowledge and the relation of knowledge to human values need not, then, require of the reader advanced knowledge in the different fields of science and mathematics; only so much acquaintance with scientific methods and results is presupposed as will suffice for an understanding of typical scientific statements or laws cited to illustrate the philosophical issues under discussion. In many books purporting to deal with the philosophy of science —especially those written by professional scientists—the philosophical issues tend to become lost because their authors try to get in a survey of all the sciences or their history, or an account of the more startling recent developments.

In the present book the emphasis is upon the philosophical interpretation of science and only enough scientific exposition is introduced to give the argument adequate illustration. Only a few technical terms, either philosophical or scientific, have been found necessary. Consequently the book should be intelligible both to students in philosophy of science courses, who come to the subject with varied scientific backgrounds, and to scientists and others interested in the nature of scientific knowledge and its function in society.

Different interpretations of science are discussed, but certain points of view are definitely favored. In epistemology and theory of reality a relativistic position is defended. My general philosophical outlook has been considerably influenced by Professors E. B. McGilvary and A. E. Murphy. On questions of value and the social implications of science a scientific humanism is favored as against any form of supernaturalism."

And yet, in my understanding of the events that followed upon Ayer's youthful (I think he says about himself) enthusiasm, if accepted in its 'pure' form, that philosophical position would have ended most of philosophical discussions. Viewers from the outside of academic philosophy, like Mencken, who was blessed with a biting but often accurate tongue, wrote that most philosophers simply talked about other philosopher's ideas (and their own) and most of it was twaddle.

Well, there seemed (to me) to be a dangerous rift in academic philosophy were the Positivists to win the battle: what would the philosophers talk about that was not nonsensical in the view of the LP's?

I'd like to return to my movie metaphor, above. If philosophy be the history of ideas; history, too, qua history, must be a prime example of metaphysics, there being no way to restart the time lines and test the conclusions of historians. Historians, then are adept at generating fables that may or may not have any relationship to actual events: I offer the Christian religions as the prime example of a fable that carried a kind of truthiness into what should have been finished with many years ago. A favorite philosopher of mine, R. G. Collingwood tried to help the historians via his book:" The idea of History," 1946.

But this is what we are--we humans; we seem to love fables. Rail against that and one is screaming at the waves of the ocean to halt.

So it is likely no-one will accept this, but I say even the study of the ancients--in the view of this now fabulous-until-discovered movie--cannot be a true dialectic; we can't have a discussion with Kant or Aristotle or Heidegger or Goethe. We are forced to make-up our impression of these historical figures based upon what they (allegedly) said and what others said about them. Is that a scientific vector? It may be as good as it can be, but it does indeed raise the validity of our imaginary movie teacher who questions whether we need concern ourselves with the ancients.

In some ways, by avoiding them, we start with a firmer foundation. For let me again return to the architectural metaphor: we have learned the things that concern the ideation of a few thinkers years ago, through rigorous experimental study. And while even the strongest of the foundation stones might be cracked at some future time, this is the best we have. Would my currently imaginary teacher be correct in avoiding study of (say) the four men I mentioned a paragraph ago? For me, it is fun to 'think' about the four and many others, but/and do I believe (see Quine) they owned a correct 'world view' at their time? And it seems that what each of us, those who think about it, does is gather an increasingly sturdy form of foundation upon which we each built our world view. I've said all this before, many times in emails, books, essays and such, and I have not deviated far from this view. Schrodinger definitely helped us by pointing out why most of us do not separately define our world view, rather we employ that world view in our very actions. In his words: "The reason why our sentient, percipient and thinking ego is met nowhere within our scientific world picture can easily be indicated in seven words: because it is itself that world picture."

With that startling observation please follow me further. I do the following because it seems foolish to re-invent something that I have already generated in a slightly different form. I will include two recent essasy, similar in scope and minimally different in aim and apologize to those who took the time to read these before this essay appeared.

I shall include some of Hanna's text here and make my comments, but my world view is better described in the connected essays. Robert Hanna: "logic is cognitively constructed by rational animals and that rational human animals are essentially logical."

"logic is intrinsically psychological, and that human psychology is intrinsically logical."

"logic is true, whereas empirical psychology deals only with human belief."

"In my opinion, the view that logic and psychology are fundamentally at odds with one another could not be more mistaken.

"So much for a preliminary internal characterization of the science of logic. But what about the specifically philosophical question about the nature of logic? My answer is that the nature of logic is explained by the logic faculty thesis: logic is cognitively constructed by rational animals."

"So, to put my first central claim yet another way, logic is cognitively constructed by all and only those normative-reflective animals who are also in possession of concepts expressing strict modality."

"Put historically, this is the Humean conception of rationality, according to which “reason is the slave of the passions.”

"rational human animals are essentially logical animals, in the sense that a rational human animal is defined by its being an animal with an innate constructive modular capacity for cognizing logic, a competent cognizer of natural language, a real-world logical reasoner, a competent follower of logical rules, a knower of necessary logical truths by means of logical intuition, and a logical moralist. This is what I call the logic-oriented conception of human rationality."

"So if I am correct about the connection between rationality and logic, it follows that the nature of logic is significantly revealed to us by cognitive psychology."

"Wittgenstein pregnantly remarks in the Tractatus that “logic precedes every experience—that some thing is so." "Wittgenstein equally pregnantly remarks in the Investigations that: [I]f language is to be a means of communication there must be agreement not only in definitions but also (queer as this may sound) in judgments. This seems to abolish logic, but does not do so."

"Chapter 3 deals with a deep problem called the logocentric predicament, which arises from the very unsettling fact that in order to explain any logical theory, or justify any deduction, logic is presupposed and used—so logic appears to be both inexplicable and unjustified."

"In chapter 4, I argue that human thinking conforms to what I call the standard cognitivist model of the mind, a model which has its remote origins in Kant’s transcendental psychology and its proximal sources in Chomsky’s psycholinguistics. This model includes representationalism or intentionalism, innatism or nativism, constructivism, modularity, and a mental language or language of thought."

My general response to these introductory statements by Bob Hanna (to his book "Rationality and Logic," MIT Press, 2006) starts with a story. When my son began his educational journey he rooted himself in the 'department of psychology' at UC Berkeley. During his journey there came events which appeared to make the word 'psychology' unutterable in polite academic circles, so there occurred a scramble to rename university buildings to something less questionable. A variety of names was employed ranging from 'neuroscience' to his current place at UCI: Institute for Memory Impairments and Neurological Disorders (UCI MIND). In that same period of time shifts in the understanding of the relationship between body and brain were undergoing changes as were studies asking about the relationship between emotion and brain and body. Was this a Kuhnian paradigm shift? Well in a way it was. Lakoff, originally a student of Chomsky and also of mathematics announced his departure from Chomsky with his first book: "Women, Fire and Dangerous Things," University of Chicago, 1987. This was his first foray into semantics and possibly his new direction into ideas concerning Embodied Minds. Ranging broadly through concepts of metaphor and mathematics he has convincingly showed that our (human) ideas of metaphor and mathematics result from the one-ness of the brain/body connection. If Lakoff and Nunez are correct, their book:"Where Mathematics Comes From," published in 2000 by Basic Books argues that conceptual metaphors generate our concepts of mathematics, algebra, and logic.

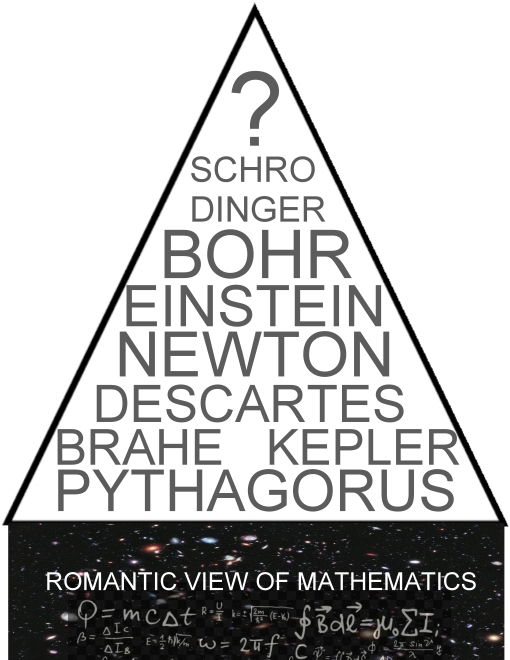

It is clear to me that for most of the scientific community whose educational experiences were formed when extensive learning in mathematics was necessary for advancement towards higher degrees and related needs. The theory of mathematics taught to most students is based upon what Lakoff and Nunez call the Romantic View of Mathematics. In their book they demolish this fable: "From a scientific perspective, there is no way to know whether there are objectively existing, external, mathematical entities or mathematical truths. • Human mathematics is embodied; it is grounded in bodily experience in the world. • Human mathematics is not about objectively existing, external mathematical entities or mathematical truths. • Human mathematics is primarily a matter of mathematical ideas, which are significantly metaphorical in nature. • Mathematics is not purely literal; it is an imaginative, profoundly metaphorical enterprise. • There is no mathematics out there in the physical world that mathematical scientific theories describe." Think, for me, for a minute, about these ideas. First the declarations above are scary to one who has placed his future in the hands of Romantic Mathematics. This would of course include every theoretical physicist in the world whose cartoon figures usually display an enormous blackboard with equations chalked upon it.

Goethe saw this early: "Men, with their figures, do contend, their lofty systems to defend." In the attached essay your will find a pyramidal scheme that is meant to demonstrate that the edifice of science finds its base--its foundation--in mathematics. There is a second cartoon that shows the idea that all of these ideas: scientific, philosophical, literary, metaphorical, poetical, ad infinitum comes from the human embodied mind--let us now call that the human. Therefore as the philosophers argue about logics and the physicists about multiple worlds, if this view becomes adopted widely the future becomes much less a predictable place. If we can make-up logics and maths and fictional science, we can make up anything.

While all this was going on a large number of 'neuroscientists' and their familiars were discovering things about the brain/body that, as Hanna foresaw, needed to be re-invited into the realm of philosophy. He says: "First, the philosophers must reopen their door and civilly invite the psychologists back in." But it no longer was it psychology, in the interval it had morphed into a real science, and a real science by any other name would smell as sweet.

In the concatenated essays there will be found references to Feynman, the physicist whose descriptions of the scientific method given in a lecture at Cornell in 1964 and by book: Feynman, Richard (1965), The Character of Physical Law, Harper and Row, New York, NY. Feynman's quotes are intensely germane and brief, showing the world what is the difference between metaphysical theory and potential truth.

I do not know what might happen if the discoveries of the cognitive scientists, the embodied mindists, and the emotionalists are taken seriously. I suspect there will be a shift, be it paradigmatic or a slight change in vector, I know not.

Here follows my promised essays:

A PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE: AFTER 65 YEARS John Cother Leissring, MS, MD Santa Rosa, CA jclfa@sonic.net www.jclfa.com; www.jclfineart.com; www.jack-leissring.info

This is a retrospective and comparative analysis of the relationship of philosophy to scientific endeavors in general, to physics and medicine specifically. I intend it as a comparative and analytic inquiry, focally annotated, into the writings by scientists from several specialities: cognitive linguistics, philosophy and theoretical physics. This is a broad inquiry into the role of philosophy in the work of scientists; given that the origins of science and philosophy share similar intentions, in the opinion of many, the scientists have left the study of philosophy to the philosophers. The discussion is also a lament about the state of theoretical physics today and offers an explanation for this state of being.

The true method of knowledge is experiment. William Blake (1757-1827)

In 1955, as a student at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, philosopher of science, Dr. Albert Ramsperger1, warned that scientists had left the philosophy of science to the philosophers. Scientists, he said, did not properly question their processes, their motives, their actions. A split developed on the pathway to knowledge with scientists taking their road and the philosophers, theirs. The diversion is important; it shows itself today in the sad state of physics with its wild theories; it also shows itself in philosophy where important ideas are dissembled, forgotten or ignored. Both are mutually exclusive echo chambers for their membership.

In the 65 years since I was a willing and thoughtful participant in understanding the meaning of ‘the philosophy of science,' new fields of study have emerged. The most significant concerns the nature of mind/brain; the picture of what is a human.

In 1936, there arose some dissenting reactions to opinions expressed by philosopher A. J. Ayer. His book, “Language, Truth and Logic,”2 is an essential exploration of philosophical errors. The book was reprinted in 1990 with new introductory remarks by the author. He admits, a youthful exuberance but feels no need to make changes in the book itself. I imagine him as the little boy who asked philosophy why the emperor has no clothes. Ayer lived within a family of philosophers and intended to live his life there. His subsequent life in philosophy describes his personality as much his intellectual tenets.

The family of philosophy does not differ from any other family. There are real and implied dominant figures, a kind of philosophic fiefdom. H. L. Mencken who knew how to turn a phrase and was a deep and intelligent thinker—a fact true of many intelligent but unlettered persons; he did not feel the effects of predefined knowledge. The educational process defines the ‘lore,’ fencing it in as if established truth. One travels the educational path by emulating or parroting the teachers who profess their opinions, often disguised as what they call facts. The panorama of pedagogical action has an old and established formality that is difficult to overcome. As long as the consumers of the educational product continue to demand persons with “degrees,” the error will continue. The reality is that neither the educational details nor the knowledge owned at graduation have any particular value to the industry who accepts the graduate. The degree process resembles a hurdle over which the student must travel attesting to his tenacity.

Mencken sees the state of philosophy in this way: “Philosophy consists very largely of one philosopher arguing that all other philosophers are jackasses. He usually proves it . . .” The realm of philosophical writing resembles this; it is accurate. What is disturbing is the tendency to assign meaning to statements made by long dead persons where there can be no way to discern what the writer/speaker might actually mean. The English barrister and writer, Owen Barfield understood this problem; his book: “Speaker’s Meaning,”32 is an invaluable stimulus. The inability to inquire of writers who have been given ascendant positions, from whom movements have resulted: Hegel, Marx, Schopenhauer, Aristotle, Plato, the Bible, whomever, makes fable of their writing. To canonize rhetorical pronouncements is a human tendency, a quality of human nature, but at best it devolves to opinion or belief. The admiration shown might be re-defined as historical curiosities, extracted from philosophical lore; it is an error to cast them as foundational. The proposals of canonized authors can simply be noted as ideas. Philosophy is the history of ideas. It is for each person to decide if the foundation of historical thinking, commonly celebrating ‘historic’ individuals, forms the proper base for the structure.

How this might be done is a problem. I often try to understand the lore of the past, to imagine how it could be that the “great” universities were established as theological schools, that is to say, using Ayer’s definition, the study of nonsense. I don’t doubt that when confronted with the problem of demonstrating non-existent entities such as gods or angels or ‘God,’ some doubt must have arisen in some minds. Doubts were concealed by clever rationalization; the erection of tautological constructs which depended upon the acceptance of an illogical posture: faith.

The cleverness with which the religious/church leaders and acolytes rendered the absurd into accepted ‘reality,’ must be given high marks; the proposals introduced, which are the very essence of metaphysical provenance, have lasted long amongst humans. The outcome: continued combat of dissenting ideas and a dark shadow over the world. The secondary losses from such fantasies produce only rare individuals who try like “chicken little” to declare the sky is falling. I would place myself in that group along with Dawkins, Harris and others, and still I realize, because of my befuddlement when I find that persons, from my childhood, with whom I spent so many delightful hours, have become, in the interval, dogmatic believers of the absurd.

Yet, I do not see these old friends differing significantly from myself in thinking ability; I must attribute to them something else. Surely the history of ideas is not limited to philosophy. A theoretical explanation for some process can become a rallying phrase for another process. The ideas of Sigmund Freud have, like those of Marx, become embedded into the fabric of human thought. The simple demonstration by Pavlov that exposing a dog to the sound of a bell could induce salivation caused thinkers like Aldous Huxley to warn against the tyrannical potentials of the conditioning process in his novel: Brave New World.”3 The nephew of Freud, Edward Berneys4 took the canon of his uncle as a method to cause people to change their minds about things, to accept, for example in 1940, smoking by women, to sell dish soap, to establish the processes of marketing in which we are now entangled. In his obituary, he was described as “the father of public relations” The “pop-ups” we fight on our computers and “smart phones,” are the result: the influences of the Berneysian hucksters. If financial success is a metaphoric marker, salespersons come-out on top. Replace financial success with, say, academic success and metaphor holds. Political success! The ability to induce others to buy things. To convince them, is a quality some intrinsically possess; I doubt if it can be taught. The gifted thus can transmit zeal, body language, acting, mendacity and more. Hitler could do it, Trump can. All the world’s a stage, said Shakespeare, and so it is.

In the history of ideas, those proposed by A. J. Ayer represent an important starting position for dealing with science, here meant as the methods of science. So although I am loath to canonize, those elements of philosophy which directly affect science are carefully rendered in his book: “Language, Truth and Logic”. I will try to summarize the basics: ideas or proposals or theories exist in two forms: analytical and synthetic. Such is the lore of philosophical lexicon, and we are stuck with it. Analytical propositions are proposals or ideas based on tautologies. They cannot be tested. They meet the lexical definition of metaphysics. They have no role in the “real world.” Ayer has pejoratively called such ideas: nonsense. Synthetic propositions or ideas or theories concern themselves with the real world and are based upon deduction from established theories (facts) or are proposals delivered for testing. The physicist Richard Feynman, in a lecture given in 1964 in Ithaca, NY, defined science this way: “In general, we look for a new physical law by the following process. First we guess it. Then compute the consequences of the guess to what would be implied if this law that we guessed is right. Then we compare the result of computation to nature, with experiment or experience, compare it directly with observation, to see if it works. If it disagrees with experiment, it is wrong. In that simple statement is the key to science. It does not make any difference how beautiful your guess is. It does not make any difference how smart you are, who made the guess, or what his name is—if it disagrees with experiment it is wrong. That is all there is to it. It is true one has to check a little to make sure that it is wrong, because whoever did the experiment may have reported incorrectly, or there may have some feature in the experiment that was not noticed, some dirt or something; or the man computed the consequences, even though it may have been the one who made the guesses, could have made some mistake in the analysis.

You can see, of course, that with this method, we can attempt to disprove any definite theory. If we have a definite theory, a real guess, from which we can conveniently compute consequences that can be compared with experiment, then in principle we can get rid of any theory. There is always the possibility of proving any definite theory wrong; but notice that we can never prove it right. Suppose that you invent a good guess, calculate the consequences, and discover every time that the consequences you have calculated agree with experiment. The theory is then right? No, it is simply not proved wrong. In the future you could compute a wider range of consequences, there could be a wider range of experiments, and you might then discover that the thing is wrong. That is why laws like Newton’s laws for the motion of planets last such a long time. He guessed the law of gravitation, calculated all kinds of consequences for the system and so on, compared them with experiment—and it took several hundred years before the slight error of the motion of Mercury was observed. During all that time, the theory had not been proved wrong, and could be taken temporarily to be right. But it could never be proved right. . .”5

That excerpt describes perfectly the nature of synthetic proposals/theories. In spite of his standing as a theoretical physicist, Feynman sometimes occupied fuzzy areas founded upon mathematics. His analogies with symbols and diagrams, like analog clock faces, provided him with a means of picturing processes, yet they were analytical in nature; the analogy does not hold for binary clocks. Feynman’s life was interesting and quite richly diverse.6

Once many years ago, I entered a retail store on the wall of which was a most remarkable statement. The statement concerned the idea of belief. I jotted the words down and later learned from the New York corporate offices that its origin was a publication by two philosophers: W. V. Quine and J. S. Ullian, under the title: “The Web of Belief.”7

The idea the authors present is simple. All beliefs are interconnected (like a web or pantograph) and we choose them for a variety of reasons. Some come as empirical knowledge—we test the world and the outcome becomes a belief. Other non-empirical ideas come at different and delicate times in our lives. These ideas are revealed stuff—religion is a biggie. The revealed material, often coming from statured individuals has favored status—it exists as if behind one-way glass. The beliefs arise in families, in religious exposure and training or from the radio or TV. These ideas cannot be changed, not readily. It is for each of us to see which of those ideas we hold are of that type. Can we rid ourselves of them?? Not easily.

I became quite enthused about this book title, and expanded the phrase in my mind as a possible explanation for much of human behavior. The book is useful, but it suffers from being the guidebook for a course of study; it adopts the pedagogical stance, with questions at the end of chapters. That annoyed me. But I found things of value in the book and took them to form my version of the Quine/Ullian proposals. In doing so, I describe the process one uses to internalize ideas from outside sources: writing, other humans, classroom work. We tend to make those ideas our own. This describes the history of philosophy. Internalized information, no-matter where it originates, creates, for each of us, what we accept as knowledge, and like a web, it connects to every other bit of information.

A departed friend thought about “information, his field of study while in University. It was his view that the English word: Information, described a process: the subject, information, was in the process of being formed. The subject of thought, the gaseous thing, the idea, the imaginary event or thing that was “seen” in the mind’s eye, in the thought bubble of the cartoonists, was in the process of being formed. Because it was malleable, it might be transformed into something else by other influences. Knowledge, information, data, was always in motion. A valuable proposal.

To get back to my childhood friends who now appear to me as ridiculous in their acceptance of the dogma of their religion, who attribute powers to nonsensical entities, who explain matters such as global warming to the powers of the god in which they faithfully believe, who have transmogrified in some bizarre way into persons with whom I can no longer have a meaningful conversation, who have become opposing champions of the scientific method—the search for knowledge. I ask how this happened, and I imagine the following: if Pavlov and Huxley are correct, and these friends, for social or other reasons attend weekly-regularly their “church,” then in the intervening seventy years or so, they have been potentially exposed to 52 X 70 events which exposed them to the lore of the church including the sermonizing. I understand that there are some Catholics who attend “mass” daily and for whom this equation is 365 X 70 events. This is akin to Pavlov ringing the bell before his experimental dog, causing the poor beast to salivate, but not for food. The outcome of such religious conditioning cannot be nil. In the 1960s we called this brain washing. I’ve experienced this; I can still remember and repeat silly phrases from childhood radio advertising, for example: LSMFT: “Lucky Strike Means Fine Tobacco.” That remembrance did not come from nowhere. Rinso White! “Ivory Soap is 99 and 44/100 percent pure. It Floats” So went the Proctor and Gamble phrase, one that originated in 1895 and pummeled me through my growth years. It is still stuck in my memory.

Expand, then, the “church/family” influence into ‘news’ sources, television sources; all are echo chambers, repeating the same often mendacious pronouncements. I have seen otherwise normally intelligent persons become influenced by the daily babble of such as Fox news, Limbaugh, whomever. The outcome is predictably inevitable. By all means, re-read “Brave New World.”

To disentangle the web of philosophy, to understand “the Philosophy of Science,” it will be necessary to confront important qualities of thinking to understand what is called “Mind.” Mind must be what those who ask about consciousness seek. Consciousness takes several metaphorical poses. Some thinkers, like Joseph Campbell21 attribute to non-human entities a kind of consciousness, as when he describes the phototropism of the flowers in his lanai in Hawaii, always pointing themselves towards the sun. If one can go to botany in metaphor, why not take from biology elements of an individual cell? Isolated cells have been shown to possess periodicity, to have internal clock-like behavior which perhaps reflects the inner clock of the human, the quotidian reaction to the earth and its relationship to the sun and the universe.

Humans, animals and plants in our earthly environment are the only forms that could result from such an environment. There is no top-down design for this. Darwin is correct.

Well, the potentials are great and are limited (only) by the mind of humans. The mind of humans may be constituted to ask questions. Questions, problems, answered for some by faith and for others, like myself, by a desire to know. This implies a desire to know everything. Can this be possible? Kerouac has poetically described: “there are so many things because the mind breaks it up.”8

In my education, I became first a physician and then a specialist in the study of disease called pathology. Amongst the subdivisions, generated by this specialization, was the field of clinical pathology, another phrase for laboratory medicine, which is another phrase for what patients learn to know as the taking of and study of blood samples, urine samples, biopsies, and stool samples. Both patients and physicians rely upon laboratory medicine to define what is normal. There are philosophical and scientific obstacles to overcome in order to understand what ‘normal’ means. I would like to describe to you the problems:

Throughout development, humans are faced with a serious question: Am I normal? While for some this question is a constant worry starting in childhood, for others it concerns only aspects of their health. W. H. Auden expressed doubt: “Health is the state about which medicine has nothing to say.” In many respects that is true. While it is essential that a practitioner of medicine know what a body free of disease ought to look like, there is always uncertainty. As technological progress is made artificial means of probing the body take precedent; the specialties of radiology and cardiology are prominent in this. But the relationship of the individual patient to the practitioner of any area of medicine and the laboratory specialist is one where the philosophy of science intersects with the science of medicine. The practitioner inquires of the clinical pathologist the state of a requested examination of a sample taken from his patient. The question implicitly asks: is this sample from this patient normal? This sounds like a completely reasonable question and is asked in that context probably at each visit a patient makes to her physician. In general, the requesting doctor is asking no philosophical questions about the test s/he is requesting and yet the absence of such inquiries is fraught with problems.

How does the referring doctor know what is normal for his patient? How does the clinical pathologist know what should be normal for the specimen taken from the patient? It is this arena where the conflicts between science and philosophy take place. Let us say the referring physician requests a test for some chemical element of the patient’s blood, say calcium. Elemental calcium is not sought; it will be a salt of calcium. The laboratory to which the patient is sent will undergo a series of steps to test for this substance. At this point the laboratory faces several questions: what is the status of the patient? That is, has the person been exercising recently?, fasting?, expressing disease apparently unrelated to the test “calcium?, are the veins of this patient accessible?, does the laboratorian know how to obtain a proper sample? is the sample collected in the proper container? has the sample been altered by contamination with damaged red blood cells? And many other matters to consider.

When this sample is obtained and properly marked and identified as originating in the patient in question, it is moved to the laboratory where proper handing is essential. For example, some hospitals use pneumatic tubes to send the specimen, which can have hemolytic effects, the sample may be carried by vehicle and subjected to heat or cold. But when finally received by the laboratory it faces again proper identification and actions. The sample might be erroneously identified or the separation of cells from the serum or plasma can be in error. Eventually a serum sample from this patient is prepared ready for analysis. The method of analysis is dependent upon the capability of the lab. There are a variety methods of determining the absolute amount of calcium salt in that serum specimen. These range from chemical analyses to methods of spectrographic testing, either emission or absorption spectroscopy. Chemical analysis employing analogous endpoints can also be used. All of these are dependent upon a background of analytic reports which discuss specific problems with each method. The method chosen depends upon the laboratory director’s interests and knowledge.

So the result has been obtained. How does one know if this value is “ normal?” The way this is achieved is a serious philosophical problem. Before I bring-up Karl F. Gauss, I wish to introduce another harmful philosopher: Plato. Plato, whose name was Aristocles, lived approximately 427-347 BCE. Personally, he was an Aristocrat, a snob, a bigot, and a man with limited perspective. He is the original idealist, one who believes that there exists in the world a ‘perfection’ to which all else must be compared. Thus, he introduced to planetary motion the idea of the perfect circle which hampered thinking until the observations of Kepler and Brahe. Plato adversely affects many to this day. Karl Friedrich Gauss lived 1777-1855. He was a mathematician, physicist and astronomer. He proposed the ‘law of errors,’ which had its unfortunate effects upon science since that era.

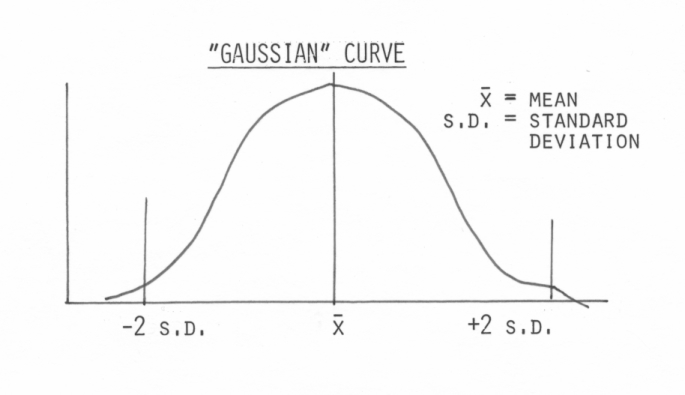

The “law of errors” can be stated this way: If repeated measures are made on the same physical object, the distribution of the random component can be well approximated by the following curve:

Please note that the idea of Gauss was to show that if one took a ruler, for example, and measured carefully the length of an object and recorded each measurement many times the recordings would show a pattern of distribution of length that would correspond to the above curve.. That is fine for measuring the height or length or weight of any object—always the SAME object, but its does not apply to distributions of measurements in groups of humans. Each human is different and unique; to lump a group of “so called” healthy humans and take from each a measure of a specific serum chemical, all things being equalized as noted above, the result is not Gaussian, and the question of estimation the ‘mean’ and ‘standard deviation’ does not arise.

Please note that the idea of Gauss was to show that if one took a ruler, for example, and measured carefully the length of an object and recorded each measurement many times the recordings would show a pattern of distribution of length that would correspond to the above curve.. That is fine for measuring the height or length or weight of any object—always the SAME object, but its does not apply to distributions of measurements in groups of humans. Each human is different and unique; to lump a group of “so called” healthy humans and take from each a measure of a specific serum chemical, all things being equalized as noted above, the result is not Gaussian, and the question of estimation the ‘mean’ and ‘standard deviation’ does not arise.Regrettably, many medical students graduate from their medical school firmly convinced that if a sample is large enough, the distribution will be “normal” (Gaussian) regardless of the measurement under study, and that 95% of the measurements will be included in plus or minus two standard deviations from the mean-the middle..9

The distributions in healthy persons are not Gaussian. Once we discard the idea that the distribution of values in healthy persons is Gaussian, the question of estimating the mean (normal) and standard deviation, does not arise.

And yet, these erroneous ideas are stuck into medicine like mathematics is stuck in theoretic physics (see below). The result is that medical science has perpetrated and continues to use erroneous data this way. In 1927, Henry Louis Rietz wrote “the followers of Gausss retarded progress in the generalization of frequency theory. . . In the decade 1890-1900 it became well established that the normal probability function is inadequate to represent many frequency functions which are seen in biologic data.”10

In 1946, H. Cramer wrote: “Everybody believes in the law of errors (Gauss), the experimenters because they think it is a mathematical theorem and the mathematicians because they think it is an experimental fact.”11 The recycling of erroneous ideas was referred to by A. V. Whitehead as the “Cross sterilization of disciplines, The bolstering up of arguments in one field with doubtful and imperfectly understood inferences made from another.” This in a nutshell observation readily describes the plight of theoretic physics. In fact Feynman, the physicist confessed not knowing the meaning of the theories of physics and simply resorted to calculations. There is something that must be satisfying to humans about performing the acts and rules of mathematics, and when we study the book by Dr. Sabine Hossenfelder,12 we will often find her referencing to the “beauty” of mathematics. And it is here that I suspect the work of Lakoff and Nunez shows its potential for shifting paradigms. To philosophers, the normal is defined by observation; among scientists it is widely believed that the statisticians have proved that the normal is X = +/- 2 S. D.”

What, then, is normal for these entities engaged in demonstrating a value of the calcium in the patient’s serum? We can try some definitions by resorting to lexicon: for some it is the average, thus meeting the arithmetical mean, for others it is a place about midway between extremes, and/or synonyms for average include mean, median and norm. Definitions of normal include “authoritative standard,” (whatever that might mean), or conforming to natural law, or finally, average; as a set of standards usually derived from the median achievement of a large group. “Normal” also connotes habitual or average or values that tend to cluster around a central point. The implication includes the opposite: abnormal when the clustering spreads further from the central tendency. We use the term normal in several senses: conformity to a type, the “quality” of a value, or as a moral judgment. But what does this discussion demonstrate to us for the purposes of understanding what the patient, the laboratory and the referring physician might understand about the result of the test?

Aside from results of testing, say of calcium, and attempting to discover whether the person’s value of calcium is indicative of any disease process, we find that further investigations of the role of calcium in the serum is understood as the process by which this element is carried in the blood stream. For example high levels of calcium can be found in association with high levels of protein, mainly albumin, which is one of the components of serum, so that an unusually high level of calcium, other things being again equal, might move one to examine the levels of serum protein.

Well, we are still far from a satisfactory definition of normal as regards this particular chemical test we have chosen to examine. We have tried to employ mathematics and find it in error. Similarly the statistical mathematician, defined by some as a person who tells you in statistics what you have told him in data, simply cross sterilizes the field by applying methods to the data. This is also erroneous.

If we try to think about any value of language that uses the word normal in its context, we might find that lurking somewhere in our understanding is an association with something called quality. If this has any validity, one might say, for example, that a person living a life of “quality” (yes, I am stuck here with a new requirement , a new definition), and that person is free of complaints about specific symptoms as concerns her body and mind, that this individual might somehow be described as in harmony with his life. Thus, a value of any given blood chemical might be considered proper for that person. Thus, in this person, who is in harmony with life, has a value of serum calcium = X. Is that a proper means of determining normal?

We find that throughout the history of medicine, study of certain molecules in the group of individuals who claim to be in ‘harmony with life’ when studied produce a “mean” or “average” or “normal” distribution which one might accept as normal for persons of that kind. For example, in the 1960s it was accepted that the level of cholesterol in the blood was normal if around 330 mg/dl. Subsequent questions raised by some who study diseases of the heart and blood vessels asked if this level was “ideal.” Was this the average concentration for all? What about groups which would later develop diseases of the heart and blood vessels. Not arguing at this time with the beliefs of the researchers—and there is ample reason to argue with their conclusions about the role of exogenous cholesterol on the body—it was found that the level of cholesterol should be lowered to less that 200 mg/dl. and the idea of a ‘normal’ or average level be discarded in favor of an ideal level. Plato again.

The outcome of all this was good news for the population groups in question. The development of better understanding of diet and its effects upon life resulted in a significant decrease in deaths due to heart and blood vessel diseases.

The end of this story is somewhat difficult: try as we may, we cannot come up with anything like an absolute definition of normal, from a scientific perspective. Therefore, we remove any individual from the Gaussian distribution curve and from the errors of statistics, which willy-nilly place her test results wherein her risks are defined by X = +/- 2 S. D.

Putting all this together might result in defining a normal person as one who is in harmony with existence and who has no specific complaints. It might be possible to say that the only criteria for ‘normal’ for any person is herself.

There are a myriad of questions and difficulties that concern the science of medicine. The current methods of delivering medical care are problematic; its diversion from philosophy can be serious, which I have hoped to show in the foregoing. I cannot avoid a personal observation: I became a medical drop-out; 20 years ago, I quit after almost fifty years of medical study. I see today that the interface between patient and doctor has been seriously altered; the interfering device is a computer screen on which is displayed,data, which the physician commonly accepts as real information, true information, factual information. Obviously this is fraught with problems. The traditional ways of learning about a patient—deeply embedded in medical history—are likely gone. Medicine is not pure science. It relies upon interaction between an observant physician and a willing patient. There are interactions which are non-verbal and which demand seeing the patient as a whole. This process is disturbed now and the consequences we will learn of later.

Trends and preferences swing us, sometimes wildly. We are now in the era of STEM, an acronym for “Science,” “Technology,” “Engineering,” and “Mathematics.” This mantra is being shouted almost to the roof-tops as if it potentiates some form of break-through. I have no specific or testable theories on why this may be so, and I shall dip into nontestables—ie. metaphysical speculation. There is something amiss because of the “smart-phone,” and other forms of hand-held devices. There is an incredible proliferation of what some call information, on the one hand, and the compression of thought into short groups of words, on the other. Without language there is no silent but verbalized thought; by minimizing word use, depth of knowledge and the breadth of understanding are punished. Here, the novelist becomes the guide: a theater, as in the Greek era, can demonstrate human frailties and dilemmas. And, too, the novelists: surely Huxley’s “Brave New World,” and Orwell’s 19843 are worthy of thoughtful analysis today. An aside: I find I "think" in pictures, not words. I have known others who claim the same, so language might not be essential for some kinds of thinking.

Yet, that analytic action will be undertaken by only those who are intrinsically aware or who are somehow directed towards analysis. I am writing this at a time when we are stuck with a president who was not democratically elected, who, with his loyalists, stole the presidency and who comes-off as a rather stupid man. But he owns sufficient charisma to maintain. We see parts of him in the Caesars: Nero and Caligula and in the evil Livia. To understand this requires a willingness to read, not tweety squibs of aphorismic babble, but to read in depth. Who will do this today?

It might seem that I am escaping from the propositions of the first paragraph: the consideration of the separation of science and philosophy. As I ponder this problem, I imagine the value of the novelist who presents in a theatrical fashion potentialities of behavior and the actualities of being. I hold high the message by Hermann Hesse in “Magister Ludi,” the “Glass Bead Game,”41 and the observations of Walker Percy in his book: “Lost in the Cosmos, The last Self-help book.”33 Hesse shows us what can happen if we lose perspective and become obsessed with a meaningless endeavor. Games can be played at many levels—disinterested neophyte to compulsive madness. One need not look too far for similarities: the card game of bridge, scrabble, Mah Jung, poker, man-made diversions often taken to extremes. Walker Percy tries to explain this behavior as a form of leaving, a transcendence, an escape from the day-to-day boredom of human and family life into a rarified world of thought. We see mathematicians, physicists, and biological scientists shifting themselves to places inaccessible to common humans, The distancing can and does cause sociological disorder; attempts to return to the prosaic life from which they flew can result in loss of humanity. The quotidian becomes their hell on earth.

Here we have the problem of explaining, perhaps explaining away, why we do what we do. We end-up relying for explanation through metaphysics, those parts of philosophy which are intrinsically meaningless—unprovable, untestable. We all do it, in one way or another. See my book: the Mystique of Metaphysics.13

I quote the writer/artist/polymath Michael Ayrton (1921-1974) “I think one of the reasons why we’ve come away from self-evident truth arises out of the ideas of the Enlightenment, and of the Cartesian philosophers in the 18th century, who made assumptions; because science is developed on the basis of causality, of what a thing is and not of why it should be—teleology——what the ancient fathers of the church were much more concerned with, we have lost the ability to see that the simple solution is not necessarily the solution. . .”14

Faux Science: Perhaps Goethe was correct when he wrote: ‘everything is metaphor,’ for emulation begets status if only conditional. I mean by this that copying the forms of a process gives credence to the copy; if it looks like a science perhaps it is a science. One of my favorite philosophers, R. G. Collingwood, attempted to analyze the nature of history—that is, scholarly writings on historical events or persons. His book on the subject is: “The Idea of History”34(1946), which proposed history as a process in which one relives the past in one’s own mind. Only by immersing oneself in the mental actions behind events, by rethinking the past within the context of one’s own experience, can the historian discover the significant patterns and dynamics of cultures and civilizations. While this idea is meritorious, it points to the subjectivity of the discipline. Yet, in the view of the philosopher Roger Poole35, subjectivity is the only process available to humans. He suggests that at each encounter with reality a person makes an ethical or moral decision dependent upon the individual’s nature, education, background, attitudes. In Poole’s sense, objectivity is a myth, a will o the wisp, metaphysical nonsense. The Princeton philosopher Frankfurt in his little book: “On Bullshit,”36 attempts to differentiate bullshit from outright lying. As he describes it, “Bullshit is unavoidable whenever circumstances require someone to talk without knowing what he is talking about. Thus the production of bullshit is stimulated whenever a person’s obligations or opportunities to speak about some topic exceed his knowledge of the facts that are relevant to that topic. This discrepancy is common in public life, where people are frequently impelled— whether by their own propensities or by the demands of others—to speak extensively about matters of which they are to some degree ignorant. Closely related instances arise from the widespread conviction that it is the responsibility of a citizen in a democracy to have opinions about everything, or at least everything that pertains to the conduct of his country’s affairs. The lack of any significant connection between a person’s opinions and his apprehension of reality will be even more severe, needless to say, for someone who believes it his responsibility, as a conscientious moral agent, to evaluate events and conditions in all parts of the world.”

But even when a person is adept at gathering data—perhaps in the parlance of Norman Mailer: “factoids,” and skilled at writing, the depth of knowledge is perforce finite. One whose life is that of a contributing writer/critic is caused to be a position of relative bullshit casting; the demands of publication and the limitations of a varied field of knowledge require this. Thus, the reader is commonly in the position of accepting a degree of bullshit simply because of the nature of critical writing and the limits of human ability.

That is not to say that we do not get pleasure and value from some critical writing, but it is, I believe, essential to realize that the writer is presenting subjective opinions. While this could be considered a continuous regression towards the mean of nihilism, nonetheless one can usually detect the flavor of subjectivity and, therefore, experience doubt. Maybe it is simply another form of entertainment where we buy magazines and books for the purpose of making the periods of daily life more interesting, more satisfying. Yet, that suggests the choices made by the reader tend to be agreeable proposals. It is the echo chamber, the hall of mirrors, we tend to occupy.

The philosopher, Jerry Fodor tried to understand the “why” of this echo chamber idea. Quoted in Steven Pinker’s book: “The Language Instinct,”15 the following was synthesized and restated for the purpose of this paper: “ Fodor begins:..I think that relativism is very probably false. What it overlooks, to put it briefly and crudely, is the fixed structure of human nature. Fodor’s words are in quotes.

1. What we know determines what we see; we interpret what we expect to see or feel in the light of our knowledge. [“cognition saturates perception”]

2. Our theories, which are plausible generalizations we make from observations, determine how we perceive experimental results. In effect interactions #1 and #2, become self-fulfilling. [“one’s observations are comprehensively determined by one’s theories”]

3. Values, guiding principles or ideals, are determined by one’s cultural milieu. The act of placing “holy water” on ones forehead is incomprehensible to an atheist or a Buddhist. [“one’s values are determined by one’s culture”]

4. One’s science, one’s general knowledge, is directly related to social rank. Social rank tends to reflect genetic or sociobiological conditions, and repeats the value the specific society in question places upon knowledge and truth. [“one’s science is determined by one’s class affiliations”]

5. One’s knowledge of how things work, the epistemology of existence, depends upon how the words are strung together in the language employed for describing this (to oneself and others). [“one’s [absolute presuppositions] are . . .determined by one’s syntax (language)”]

Because perception is saturated by cognition, observation by theory, values by culture, science by class, and beliefs by language, rational criticism of scientific theories, ethical values, world views, or whatever can take place only within the framework of assumptions that—as a matter of geographical, historical, or sociological accident—the interlocutors happen to share.15

This aspect of human nature is a dark shadow.

Studying a critical review of several books about Abraham Lincoln by Adam Gopnic (which appeared in The New Yorker, September 28, 2020, I find that I enjoyed Gopnic’s prose and yet I question how the writers of the reviewed books know, even quasi-scientifically, facts about Abraham Lincoln. It is a given that history of this kind is intrinsically metaphysical, it expresses the author’s presuppositions. It is a truism that most of us like to believe that we are able to see another human for what s/he is. This is the subjective interface referred to by Roger Poole. We make ethical and moral decisions about other humans all the time. The writer Walker Percy once asked: “One of the peculiar ironies of being a human self in the Cosmos: A stranger approaching you in the street will in a second’s glance see you whole, size you up, place you in a way in which you cannot and never will, even though you have spent a lifetime with yourself, live in the Century of the Self, and therefore ought to know yourself best of all.” I wonder if someone like Trump ever sees himself as others see him. Thank you Bobby Burns.

Intelligence/ability ranges over all life style choices: philosophers and physicists are not privy to special status. How, then, is a career choice determined? I assume it’s causality which reflects all aspects of human development to include social, familial, genetic, experiential causes. Yet it appears that society at large gives, at differing times in history, preferential status to some careers and denigrates others.

Let’s talk about world views. Schrodinger.[infra]

Novelists help us understand those historical periods when it was common to treat children differently depending upon their sex and their position in the birth order. There was likely a “reason” for this, though it is hard to understand today. The status of the female child was in historical times subjacent to the male and the status of the female today remains difficult. Do we explain these things by habit, by logic, by decree? However they be analyzed they are problems. And, given that intellectual capacity ranges and is distributed in all of these categories, it seems surprising that the status quo was accepted. And it is the “why” of this phenomenon that becomes the necessary question.

So it is that originating from a putative family unit, the offspring emerge, like butterflies from their chrysalis to become philosophers, novelists, mathematicians, physicists, mechanics, engineers, poets, theologians. All of these I say own an intellectual capacity somewhere along the distribution curve metaphorizing that quality, so they present to the world degrees of intelligence likely comparable to any imagined or examined distribution.

In that distribution lies a spectrum of choice. There are academics who study choices. Pure determinism I place on the back-burner. The result of such studies shows differing qualities of interest or intention. The poet may have minimal interest in mathematics, yet be quite capable of mastering its rules. Choices. Only those appear important.

The psychologist Michael Moscolo presents a summary of his proposals concerning conscious agency and the following abstraction from his paper: “Is it possible to reconcile the concept of conscious agency with the view that humans are biological creatures subject to material causality? The problem of conscious agency is complicated by the tendency to attribute autonomous powers of control to conscious processes. In this paper, we offer an embodied process model of conscious agency. We begin with the concept of embodied emergence – the idea that psychological processes are higher-order biological processes, albeit ones that exhibit emergent properties. Although consciousness,experience, and representation are emergent properties of higher-order biological organisms, the capacity for hierarchical regulation is a property of all living systems. Thus, while the capacity for consciousness transforms the process of hierarchical regulation, consciousness is not an autonomous center of control. Instead, consciousness functions as a system for coordinating novel representations of the most pressing demands placed on the organism at any given time. While it does not regulate action directly, consciousness orients and activates preconscious control systems that mediate the construction of genuinely novel action. Far from being an epiphenomenon, consciousness plays a central albeit non-autonomous role in psychological functioning.”17

Mascolo imagines the means whereby conscious agency becomes a choice-making element of humans without attributing to any specific quality along the human spectrum. This is an explanation without testable end-point, yet is helpful to dislodge the invocation of extra-human influences. Perhaps only that.

It is necessary to explain certain human qualities that remain difficult and mysterious. How should it be that chemicals, including those produced by the human being, produce changes in human consciousness? The effects of products of the ductless glands such as estrogen and testosterone undoubtably influence behavior—the literature supports this. Psycho-active drugs and medications induce well-described conscious/psychic activities. We know few substantive facts about hypnosis, yet there is a large library of reports suggesting the phenomenon can result in marked alteration of specific physiologic reactions: pain, for example. It is claimed that under hypnosis, surgical operations can be performed, physiologic functions can be altered: heart, rate, blood pressure.31 Thus, by focusing only upon certain categories as presumed examples of ‘humanness,’ we are perhaps fooled into explanations that are certainly incomplete. If intrinsic and extrinsic chemicals can induce changes in behavior, what then of external influences?

We thank Pavlov for the idea of conditioning without giving implications of ‘conditioning’ the required thought. Aldous Huxley did; we tend to forget him despite the significance of “Brave New World.” Thus we tend not to find, nor form, possible explanations for certain human actions or we ignore the implications examining the influences of processes which a given individual might undergo.

I say this is particularly important in the era of now, where we see a unique avalanche of data and information impinging upon us; for reasons of preference the populus divides itself into groups that are intrinsically competitive.

The Psychiatrist Ronald Smotherman suggested that the “purpose of the mind is to be right.”18 That is teleology, in science, not allowed. Purposiveness in nature raises the idea of a quality of being towards which an organism aims; this is a sweet idea but fuzzy. If one changes the idea to this: When the mind/brain has made a decision, it forever holds that decision as correct. It does everything in its power to retain that decision, even to the disadvantage of the body it serves. If the mind/brain is the guiding element of a person’s existence, this need to be right about choices and decisions becomes seminal. Having to be right may in the end lead to destruction of the body the brain protects. Sunni Moslems must be “right” about their beliefs and are in opposition to Shia Moslems, creating thereby, conflict, war, destruction. The Catholics oppose the Protestants, Lutherans say they are right. Everyone opposes the Jews. Each of the groups believes it is right.

And, so it goes.

But I speak here mainly of religious beliefs, which I have shown elsewhere to be nonsense—in a philosophic sense. I can equally entertain descriptions of strongly held beliefs in academics of many sorts: physicists, philosophers, writers. Does the physicist have a choice? One whose educational history includes a deep exposure to mathematics, mathematics that is so rich with the belief it is the study of a quality of the universe, something “out there.” This is educational conditioning and assures the physicist’s explanation, her reality. It becomes his world view. What if mathematics were a tautology, a game, a made-up process, a deep metaphor? What would be then the nature of physics—theoretical physics? Dangerous question.

George Lakoff and Rafael Nuñez examined the origins of mathematics and conclude mathematics to be a reflection of the “embodied mind/brain.” Their book: “Where Mathematics Comes From.”19 is an essential source to discover the nature of the mathematical processes embodied in the human brain. The implications of this knowledge are important; they directly effect the whole of physics which bases itself—the theoretical parts of physics—upon mathematical “truths.” These truths, which in the light of Lakoff/Nuñez are merely the world views of the person who uses mathematics as her guide. We will examine the conclusions of Lakoff and Nuñez later in this book There are cracks in physics, to be sure, and they are widening as a larger number of practitioners question the validity of mathematical analogy. This should be obvious to anyone who considers common claims of mathematics, such as time reversal and symmetry. Time does not go backwards. Time breaks things, it does not repair things.

This amazing loss of perspective as regards theoretic physics, I say is also present in logics, in theories of behavior, theories of music, theories of history, theories of literature, theories of religion—everywhere.

I have reported this personal experience elsewhere, but I admit to having believed myself to be “in love,” with a young woman when I was about 18 years of age and a new student at the University. She, a “catholic,” and I with no religion, urged that I undertake “religious instructions.” I was moved to do so and met weekly with a young priest in Milwaukee for an hour or so. During one of the sessions, I, still not convinced, asked him “what if all this story you are telling me is a fable? He replied that “Then my life will have been wasted.”

The suggestion by Dr. Smotherman comes full here. A belief preferred by the mind influences the whole life of the body. It’s a nice story; Sir Francis Bacon said: We believe to be true what we prefer to be true.”

In an era of unhinged politicians it is possible to become influenced and lose perspective. Yet I describe my own limited accession to what is currently defined as news by most people: I suspect that an early influential book I discovered on my Grandfather’s bookshelf when I was about 14 or 15 had much to do with my consequent life. The book, still in print, is titled: “Think for Yourself,” by R. P. Crawford,193737. The book has the configuration of a “self-help” book which includes blank pages where one is urged to write thoughts. When I return to the original volume I see my youthful writing. The methods pushed by the author to examine one’s own ideas must have stuck with me, for since then I tend to be very critical, questioning, about rhetorical pronouncements. I would try to describe to you a “movie” I run inside the cartoonist’s thought bubble that is my mind in action. For example the problem of TV formats: when I see a talking head on a TV screen, I try to see the stage set-up with the cameras and the carefully placed monitor which the head is reading and the mouth is parroting. All the while I am asking “how do you know this?” “who wrote that stuff you are reading?”and also imagining the source of the monitor writing to be someone else whose motives we cannot discover. In effect what I perceive is simply a play-act which is aimed at convincing me (and the other viewers) of some rhetorical babble. While I disdain the human tendency to give importance to historical individuals whose motives are impossible to test, I do appreciate and recommend the dialog by Aristotle on the agenda of rhetoric.20

These ideas are germane today, especially since I am writing this in the midst of the most incredible rhetorical buffoonery the world has witnessed in modern and post-modern times: The “so called” presidential debates. They are laughable, and yet fearsome as well, for as in Aristotle’s view the listener is a part of the process; we have already shown that reason or fact does not alter fixed ideas. We are stuck with the parable of the unclad emperor and the little boy.